Baseball, and its many unwritten rules

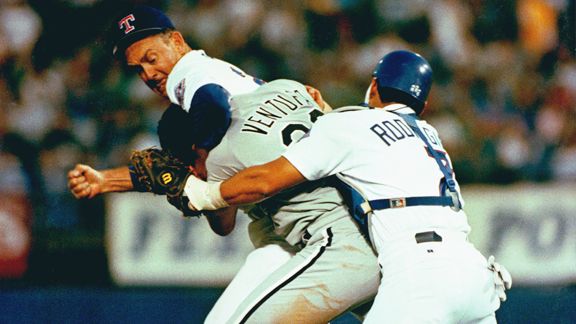

AP PhotoRemember the legendary manhandling of Robin Ventura by Nolan Ryan? A baseball code was involved.

AP PhotoRemember the legendary manhandling of Robin Ventura by Nolan Ryan? A baseball code was involved.When Phillies shortstop Jimmy Rollins was a rookie in 2001, he hit a home run off Cardinals reliever Steve Kline and celebrated by flipping his bat -- a gesture that sent Kline into a rage, screaming at Rollins as he rounded the bases.

"I called him every name in the book," Kline said. "That's [bleeping] Little League [bleep]. If you're going to flip the bat, I'm going to flip your helmet next time. You're a rookie, you respect the game for a while. There's a code. He should know better than that."

Even if Kline's reaction seems childish, it's telling how the situation was resolved. According to "The Baseball Codes: Beanballs, Sign Stealing, and Bench-Clearing Brawls: The Unwritten Rules of America's Pastime" -- a new release by freelance sportswriter Jason Turbow -- Kline's anger was assuaged when on-deck hitter Scott Rolen, then the Phillies' third baseman, told Kline that the "Phillies would take care of it internally."

Rolen and Kline, opponents in the traditional sense, were on the same page when it came to The Codes -- a long-standing system of hazy regulations that helps players and coaches police the game (often with a tinge of frontier justice). At base, it's about "three simple things. Respect your teammates, respect your opponents and respect the game," said former Diamondbacks manager Bob Brenly.

If The Codes were always that black and white, baseball would probably be the sport with the least colorful stories. Instead, it probably has the most; and what gives it that color is "the gray area," in which players and managers look at the same situation and come to different conclusions.

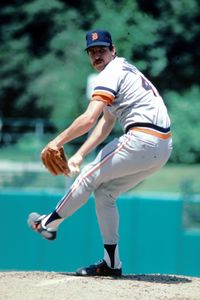

Take longtime pitcher Jack Morris' reaction when a runner at second base was stealing signs and relaying them to the batter. Morris, as Turbow relates, walked over to the runner and said, "I'm throwing a fastball and it's going at him. Make sure you tell him that." Then he delivered the pitch, knocking the hitter down as promised. At that point, Morris made a second trip over to the runner. "Did you tell him?" he yelled. "Did you?"

In stealing the signs, the runner probably thought he was being savvy; Morris, however, thought he was being disrespectful -- not for the initial action, but for continuing to do it once he'd been nabbed.

"If baseball is a business, cheating has become little more than a business practice, and, like sign stealing, is generally abided as long as it stops once it's detected," Turbow wrote.

But without someone like Dr. Phil to mediate, communication can break down, often with memorable results.

Remember when Robin Ventura charged the mound and got emasculated by Nolan Ryan in 1993? As Turbow tells it, Ryan's headlock beatdown of Ventura was the result of Ventura's half-hearted attack. Ventura wasn't really that angry at Ryan for hitting him; he was simply a pawn in a three-year-old feud between the Rangers and White Sox, which was enflamed when Jack McDowell said in the clubhouse on the day of Ryan's start: "He's been throwing at batters forever, and people are [too] gutless to do anything about it."

Enter Ventura, sacrificial lamb.

"Robin really didn't want to charge him," White Sox teammate Frank Thomas said. "It was just one of those things where we all knew he was going to drill him, and once it happened he reacted."

The situation was a direct result of The Codes -- the White Sox felt Ryan was disrespecting them, so someone needed to do something about it. If Ventura hadn't rushed the mound, he'd have lost face with his teammates.

"People inside baseball understand appropriate doses of retaliation, but the practice represents a level of brutality that simply doesn't translate in people's lives," wrote Turbow, 39, a San Francisco-based writer who interviewed hundreds of players, coaches, scouts and former players for the book. Michael Duca, who came up with the idea for the book, also helped conduct interviews.

The tales are plentiful and oftentimes hilarious, and the writers did a commendable job in using old books, newspaper accounts and original interviews. Beyond beanballs, we get behind-the-scenes stories about how (and how not) to slide, whether to talk during a no-hitter (Bert Blyleven did, and he still got his no-hitter), and the ethics of cheating, which former manager George Bamberger tackled by saying, "A guy who cheats in a friendly game of cards is a cheater. A pro who throws a spitball to support his family is a competitor."

Notably absent from the book is the topic of performance-enhancing drugs. Turbow said an early draft contained a chapter on steroids, greenies and other PEDs, but ultimately, he said, "The code surrounding that was not pervasive enough, didn't have as much to do with the game on the field as the other things. Combined with the fact the steroids issue is so big and so deep and so complex that I couldn't begin to do it justice in a chapter in this book, it just seemed wise to avoid it altogether."

Turbow interviewed baseball people as they came through San Francisco over the past five years, including former Oakland Athletics outfielder Dave Henderson, who said Rickey Henderson's notoriously weak throwing arm was the direct result of his showmanship. Some pitchers took offense to Rickey's flashy style, even if he meant nothing personal by it, and they retaliated by drilling the right-handed hitter in the left arm -- which, in Henderson's case, was his throwing arm.

"Everybody used to get on him about missing the cutoff man and having a weak arm, but that's because it was always so swollen," Dave Henderson said. "When your elbow's pregnant, it's hard to throw."

Turbow said many of today's younger players don't have the same understanding of The Codes -- and part of that is because of Major League Baseball itself, which has tried to legislate retaliation out of the game. Umpires issue warnings at the first sign of trouble, which hampers the checks and balances inherent to the old-school system.

"The Code is fading a little bit," Turbow said. "Players are becoming more friendly with each other. They share agents. They play in charity golf tournaments together. They go on vacations together in the offseason. They change teams every few years, so everyone has friends in every clubhouse. And with this level of personal civility, there's less of a need to enact a code to regulate civility.

"The old-school guys see this code kind of fading, and I think it's important to them to bolster it somehow. And talking about it is a way to make sure people know what it is, what it was and what it can be."

Cam Martin is a contributor to Page 2. He previously worked for the Greenwich (Conn.) Time and The (Stamford, Conn.) Advocate, and has written online for CBS Sports and Comcast SportsNet New England. You can contact him at cdavidmartin@yahoo.com.

|

| • Philbrick: Page 2's Greatest Hits, 2000-2012 |

| • Caple: Fond memories of a road warrior |

| • Snibbe: An illustrated history of Page 2 |

| Philbrick, Gallo: Farewell podcast |

-

TOOLS

- Contact Us

- Corrections

- Daily Line

- RSS